Including 17-year-olds in juvenile jurisdiction is consistent with legal trends based on adolescent development and is an efficient use of juvenile court resources, producing safety and economic benefits.

BRAINS, BEHAVIOR, AND THE LAW

Parents of teenagers often deal with moody and impulsive behavior that can be infuriating and has historically seemed inexplicable. Over the last decade, however, scientists have drastically expanded our understanding of adolescent brain development. We now know that the brains of 17-year-olds are still developing, causing 17-year-olds to engage in risky and impulsive behavior, particularly in conjunction with peers. This explains why even a straight-A student with an impressive résumé of volunteer activities and a talent for the trombone can be prone to that one reckless night of riding around in a car with a friend who has been drinking. Young people can be incredibly clever and clueless at the same time-even the most responsible teenagers have a combustible combination of youth, opportunity, and still-developing judgment.

There is a reason that a teenager may at times seem blithely unaware of sensible decision-making:the brain isn't fully wired-even at seventeen, it's still deep into the process of remodeling itself and maturing toward adulthood. Modern brain scanning technology has enabled scientists to understand how the brain changes over time. Based in large part upon these findings, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that all 17-year-olds, even those who commit the most serious crimes, must be held to a different standard of accountability than adults.

Adolescent Brain Development Research: Youth are Different

In recent decades, behavioral and physical sciences have demonstrated that youth are simply and significantly different from mature adults. Youth make decisions differently (and thus engage in risky or criminal conduct) for different reasons than those of adults. Fortunately, youth are also capable of significant positive growth and change, often simply by "growing out of it." Specifically, current behavioral research indicates that, compared to adults, 17-year-olds are (1) more prone to risky behavior; (2) less capable of impulse control; (3) less able to regulate emotions; (4) less able to engage in moral reasoning; (5) less able to consider the long term consequences of their actions; and (6) more prone to the effects of stress and peer pressure. Scientists have demonstrated that these differences are caused by the biological properties of adolescent brains.

Researchers examining high-resolution images of adolescent brains using MRI scanners have made two complementary observations. First, the frontal lobes of 17-year-olds are less developed than adults. The frontal lobe is responsible for making decisions, assessing risk, controlling impulses, making moral judgments,considering future consequences, evaluating reward and punishment, and reacting to positive and negative feedback. Second, because the frontal lobe is less developed, 17-year-olds rely more heavily on the amygdala and other parts of the instinct-driven limbic system to make decisions than adults do. The amygdala, located deep within the temporal lobe,is one area of the brain associated with strong negative emotions, including impulsive and aggressive behavior. The amygdala develops in early childhood and is responsible for our "fight or flight" response. The amygdala "evolved to detect danger and produce rapid protective responses without conscious participation." These two findings are supported by imaging studies that show teens struggling to reason through a dangerous scenario, while adults identify and react to a bad idea with considerably less effort expended in the later-developing frontal lobe.

As the brain continues to mature through late adolescence and young adulthood;

- [W]e get better at integrating memory and experience into our decisions. At the same time, the frontal areas develop greater speed and richer connections, allowing us to generate and weigh far more variables and agendas than before. When this development proceeds normally, we get better at balancing impulse, desire, goals, self-interest, rules, ethics, and even altruism, generating behavior that is more complex and, sometimes at least, more sensible. But at times, and especially at first, the brain does this work clumsily. It's hard to get all those new cogs to mesh.

Adolescents are intelligent and perfectly capable of making many responsible decisions, particularly when using "cold cognition" (analysis done in settings with low emotional stimuli), but applying reasoned thought to emotionally-stimulated decisions made in the moment (using still-developing "hot cognition" skills) is far more difficult. The challenges adolescents face when responding to a problem using "hot cognition" are exacerbated by other changes taking place during teenage development, including "[h]hormonal changes related to developing sexual maturity." In these cases, and based on the stage of their brain development, adolescents are more likely to act on an urge and less likely to think twice, change their minds, or pause to consider the consequences of their actions. The implication of these findings is clear: because the brains of 17-year-olds are predisposed to making more impulsive, aggressive, and shortsighted decisions than those of adults, 17-year-olds are physically unable to make the same type of reasoned and responsible decisions we expect of adults. Or, as noted juvenile psychologist Laurence Steinberg put it, "[d]during the time these processes are developing, it doesn't make sense to ask the average adolescent to think or act like the average adult, because he or she can't-any more than a six-year-old child can learn calculus."

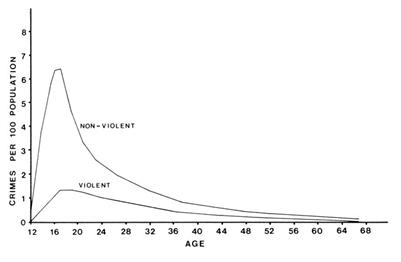

Furthermore, adolescents engage in risker behavior because their psychosocial maturity-which is measured by impulsivity, risk perception, sensation-seeking, future orientation, and resistance to peer influence-develops later than basic intellectual ability.

[Information and details about the graphic chart, please contact Heidi Mueller, Executive Director, Juvenile Justice Commission, Office of Community and Positive Youth Development, Illinois Department of Human Services, 401 S. Clinton, 4th Floor, Chicago, IL 60607, email:

heidi.mueller@illinois.gov]

As the figure indicates, basic intellectual abilities reach adult levels around age 16, long before the process of psychosocial maturation is complete-well into the young adult years. This means that adolescents are more vulnerable to peer influences and more susceptible to risk-taking behavior than adults. The confusing differential between intellectual and psychosocial ability for older teens is directly relevant when holding youth accountable for destructive behavior and attempting to prevent it in the future, including through court sentencing. Adults are constantly tempted to mistake teen intellect-school smarts-for accelerated maturity ("I know you know better than that") and may perceive actions as less opportunistic or impulsive and more calculated, punishing accordingly and concentrating less on devising opportunities for youth to practice and develop impulse control or peer resistance strategies.

United States Supreme Court Findings: Reduced Culpability and Strong Capacity for Positive Growth

Since 2005, the United States Supreme Court has explicitly recognized and relied upon the emerging adolescent development research in ruling that youth are fundamentally different from adults and must be treated differently under the law. In Graham v. Florida, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that because of the biological differences between adolescents and adults, all 17-year-olds are categorically less culpable than adults. Because 17-year-olds are still developing, they "are more capable of change than are adults, and their actions are less likely to be evidence of 'irretrievably depraved character' than are the actions of adults." As 17-year-olds become older and their brains finish developing, they will obtain the capacity to make reasoned and responsible decisions: "[t]he evidence now is strong that the brain does not cease to mature until the early 20s in those relevant parts that govern impulsivity, judgment, planning for the future, foresight of consequences . . . ." Because youth are capable of remarkable positive change and growth and can benefit greatly from rehabilitative services and support, the Supreme Court has therefore made it clear that minors should be given the opportunity and resources to rehabilitate.

Crucially, from 2005-2012, the Supreme Court has issued four successive opinions affirming the principle that youth (defined as minors under 18)are different from adults and should be treated differently. Even when explicitly presented with opportunities to draw legal distinctions based on different constitutional rights, the nature or severity of an offense, or being 17 as opposed to 15, the Supreme Court consistently chose to deliver opinions stating that, while offense and age are relevant in many respects, minors are still minors, not adults. Indeed, "none of what [Graham] said about children-about their distinctive (and transitory) mental traits and environmental vulnerabilities-is crime-specific." Offense severity does not turn children into adults.

The Illinois juvenile justice system was created to accommodate the distinctive juvenile level of culpability. The system emphasizes both accountability and rehabilitation, acknowledging that adolescents are less culpable and more capable of change than adults. Juvenile court principles, such as capacity-building and confidentiality, permit youth to transition into productive adulthood after they have successfully completed their period of supervision and matured out of their delinquent behavior, and most will. Because all 17-year-olds, including those arrested for felony offenses, are less culpable and have a greater chance of rehabilitation than adults, juvenile court jurisdiction should be extended to include all 17-year-olds.

SAFETY BENEFITS

The Commission's analysis has revealed that keeping 17-year-olds in the juvenile justice system will not reduce public safety in the short term, can enhance long-term community safety, and can ensure youth safety while in the justice system. This analysis has produced four inter-related findings:

- Research on youth "desistance" from crime shows marked similarities between reoffense patterns of younger adolescents and 17-year-olds, thus supporting similar approaches with these groups of young people;

- Studies of youth transferred to adult courts indicate higher recidivism rates than similar youth handled by juvenile courts, suggesting that handling youth in adult systems can increase risks to public safety;

- There is no evidence that prosecuting youth as adults "deters" youth crime; and

- A significant body of research demonstrates that youth are safer in juvenile facilities in comparison to adult facilities and systems.

Most 17-Year-Olds Can and Do Stop Offending

A great proportion of youth programming, prevention, and juvenile justice policy focuses primarily or even exclusively on the youngest and lowest-level delinquent youth. Some early intervention and support programs are worthwhile investments in youth, but the juvenile justice system is not intended only, or principally, for addressing low-risk youth offenders who would most likely abandon illegal activity as they mature without any intervention (see figure). Too often, juvenile justice policymakers rely on two false assumptions: 1) that interventions are certain to benefit, or at least not harm, low-risk youth; and 2) that "the vast majority of offenders at the more serious end of the justice system are uniformly treading down the path of continued, high-rate offending." Studies of serious adolescent offenders as they transition from adolescence into early adulthood show otherwise.

[Information and details about the graphic chart, please contact Heidi Mueller, Executive Director, Juvenile Justice Commission, Office of Community and Positive Youth Development, Illinois Department of Human Services, 401 S. Clinton, 4th Floor, Chicago, IL 60607, email:

heidi.mueller@illinois.gov]

Pathways to Desistance, a critical federally-sponsored longitudinal study, followed 1,354 serious juvenile offenders aged 14-18 over a period of seven years. The study was limited to youth found guilty of at least one serious (almost exclusively felony-level) violent crime, property offense, or drug offense. Instead of a uniform path, several markedly different trajectories for felony-convicted youth emerged; a small portion of youth maintained a high level of criminality (persisters), but over 91 percent reported decreased or limited illegal activity during the first three years following their court appearance. Most youth who had committed felonies greatly reduced their offending over time. A significant portion of those with the highest levels of offending reduced their reoffending dramatically (desisters). This finding of the Pathways to Desistance study is very clear: "[t]he most important conclusion of the study is that even adolescents who have committed serious offenses are not necessarily on track for adult criminal careers."

Particularly relevant to Illinois juvenile justice policy and our state's jurisdictional split for felony-charged 17-year-olds, the rates of rearrest, reported antisocial behavior, and persistence in criminal activity are not significantly different between serious youth offenders at age 14, 16, and 17.

In other words, 17-year-old felons are no less likely candidates for rehabilitation through juvenile court intervention than are younger serious offenders, as measured by their patterns of future criminal behavior. The 17-year-olds had similar static risk factors (parent criminality, mental health, and antisocial history) as the 14and 16-year-olds and significantly lower rates of one risk factor (antisocial attitudes). At the same time, the 17-year-olds "were at higher risk than the other two age groups concerning . . . factors that increase their likelihood of continued offending, but are also addressable with targeted interventions (peers, school, and substance use)."

Because lower levels of substance use, higher stability in living arrangements, and work and school attendance are related to higher rates of desistance in general and are particularly relevant to the risk factors common among 17-year-olds, juvenile court is appropriate. Interventions that incorporate substance abuse treatment into community-based services and emphasize school continuity may be particularly well-suited to reduce serious offending among 17-year-olds.

Youth in Adult Court Recidivate More

The existence of discretionary transfer laws around the country present a unique opportunity to directly compare the effects of the adult and juvenile systems, allowing comparisons between similarly situated defendants-specifically examining how each system impacts recidivism rates. Studies about transfer laws and recidivism are therefore instructive in analyzing system effectiveness to inform juvenile jurisdiction policy.

Conclusions from a Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) Task Force suggest that recidivism rates for youths who have been sent through the adult system are far higher than those of similar youths who remain in the juvenile system. Through a comprehensive review of every published or government-conducted study on transfer policies, the CDC found that a youth was 34 percent more likely to be rearrested after going through the adult system.

The CDC is not alone in these findings. In its June 2010 Bulletin, the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) also compiled results from several large studies on the impact of youth in adult court. The Bulletin examined six studies in total. Each study involved between 494 and 5,476 teens; youth were matched into pairs, where one member was sent through the adult system while one remained in the juvenile system. The nearly-identical "pairings" closely matched multiple variables, including: geography, age, gender, race, gang involvement, number of previous juvenile referrals, most serious prior offense, current offense, victim injury, property damage, use of weapons, etc.

The results are staggering. Every single study examined by OJJDP showed higher recidivism for youth in the adult system, even when youth were given probation instead of incarceration. Though there are many potential reasons for this increased recidivism, some significant factors impacting youth include: stigma associated with felony convictions; fraternization with adult criminals; incarceration trauma; lack of rehabilitation focus in adult facilities; de-emphasis on family support more available in juvenile system; feelings of injustice; loss of employment opportunities post-incarceration, and the associated decrease in lifelong earning potential.

Youth May Not be Deterred by Adult Consequences

While transfer laws were intended in part to deter youth from serious crime, there is no evidence this is the case. A recent study conducted by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice found that in states that allow fair comparisons (i.e. where all 17-year-olds are originally subject to juvenile court jurisdiction regardless of the charges), transfer to adult court "bears no relationship to changes in juvenile violence," which continues to drop nationally. In fact, "to the extent that transfer policies are implemented to reduce violent or other criminal behavior, available evidence indicates that they do more harm than good [and] the use of transfer laws and strengthened transfer policies is counterproductive to reducing juvenile violence and enhancing public safety." One obvious reason for such disparity between intent and effect is simply that adolescents "are at a fundamentally different developmental stage than adults." Immaturity is relevant not only in assessing culpability, a tenet long-established within the juvenile justice system, but also in evaluating the efficacy of deterrence. As such, deterrence strategies between the two groups are not interchangeable; the notion that a threat of being transferred to the adult system acts as a deterrent for juveniles appears unsubstantiated. In fact, research on adolescent development generally, and brain development specifically, "suggest[s] that incomplete decision-making capacities, low impulse control, and the power of peer influence help explain why [both] the threat and experience of adult court do little to deter juvenile actors." As discussed earlier in this report, certain parts of the brain, particularly those governing self-control and rationality, continue to develop well beyond the age of 18.

Perhaps the most significant implication of these findings is that "[l]aws that make it easier to transfer youth to the adult criminal court system have little or no general deterrent effect[, as y]youth transferred to the adult system are more likely to be rearrested and to reoffend." If preventing recidivism and promoting deterrence are important public safety goals of the criminal justice system, policies that keep youth in the juvenile justice system wherever possible must be pursued.

The Adult System is Dangerous for Youth

Studies unequivocally demonstrate that youth accrue major safety benefits from being sent through juvenile court and juvenile facilities as opposed to adult facilities. Whether or not youth in adult facilities are housed with the adult population or whether they are kept separated from the adult population, adult facilities are clearly far more dangerous for youth than juvenile facilities. As stated by the National Institute of Corrections within the U.S. Department of Justice, "[j]ail administrators can face a difficult choice on this issue: They can house youth in the general population where they are at a differential risk of physical and sexual abuse, or, house youth in a segregated settings where isolation can cause or exacerbate mental health problems." Moreover, whether or not youth are isolated in adult facilities, they face challenges simply because adult facilities are not intended, and thus not equipped, to deal with youth.

When youth are housed with the general adult population, they are subjected to heightened risk of physical and sexual abuse. Regarding sexual violence, the U.S. Department of Justice's Bureau of Justice Statistics has found that state prison inmates under 18 are eight times more likely than the average state prison inmate to suffer sexual abuse from another inmate while in prison. Furthermore, there is a significantly higher risk that youth will be physically abused in adult facilities, with studies suggesting that youth in adult facilities are "twice as likely to be beaten by staff and fifty percent more likely to be attacked with a weapon than minors in juvenile facilities."

The second option, isolating youth from the general adult jail and prison populations, can aggravate the mental health issues that many youth already face. In addition to causing or exacerbating mental health problems, isolation can lead to cutting and self-harm. Indeed, "75 percent of all deaths of youth under 18 in adult jails were due to suicide." Furthermore, isolation can also cause other physical harm, because the lack of adequate exercise and inadequate nutrition stunt the growing teenage body. Finally, isolation deprives youth of basic programming and services, thus causing lasting social and developmental harm to the youth.

ECONOMIC BENEFITS

Raising the age of jurisdiction for felony charges can be expected to have long-term economic benefits for citizens of the state of Illinois-even more so than raising the age for misdemeanors.The juvenile justice system has higher up-front costs than the criminal justice system, but the economic destruction caused by an adult felony conviction is avoided, along with its rippling affect through families and communities. Additionally, the lower recidivism rate of youth in the juvenile justice system creates additional cost savings to crime victims, taxpayers, and state correctional agencies.

Analogous Cost-Benefit Analysis

In 2011, the VERA Institute of Justice performed a cost-benefit analysis of North Carolina's proposed plan to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction from 16 to 18, concluding that the economic benefits of the plan to raise juvenile jurisdiction in North Carolina outweighed the economic costs. It is important to note that although crime, including juvenile crime, has been declining nationwide for three decades, the study does not consider any future declines in crime other than those directly attributable to reducing recidivism via the juvenile court, and thus overestimates system costs of raising the age.

The study estimated the costs of the plan to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction by looking at its impact of the change of law enforcement, the courts, and the juvenile justice system. It calculated considerable increases to the costs of the juvenile system, anticipating additional burdens to courts and law enforcement due to the increased demand of juvenile arrests and case processing.

However, the analysis showed that the benefits to taxpayers, to victims, and to youth outweighed the costs of raising the age. With regard to taxpayer benefits, lower recidivism rates for juveniles mean that fewer people are likely to be arrested in the future, which in turn means fewer people referred to court. Furthermore, taxpayers would save money based on lower use of adult jails and prisons. Crime imposes substantial costs on victims and because of the lower recidivism rates of juvenile offenders, crime will be reduced and consequently the monetary losses to victims will also decline. Finally, the study found major benefits, especially better employment prospects, for youth. Importantly, these additional earnings generated by youth will in turn mean more taxes paid to the state. While the study pointed out that the family and communities of youth would also benefit from the policy change, the study did not include any of these benefits in the analysis because of the difficulty of monetizing them.

Costs and Benefits (in Millions) of Adding 30,500

North Carolina Youth Aged 16-17 to Juvenile Jurisdiction

| Recidivism Reduction |

|---|

| 30% | 40% |

|---|

| Direct Taxpayer Costs | $(70.90) | $(70.90) |

|---|

| Direct Taxpayer Benefits | $ 29.00 | $ 32.70 |

|---|

| Avoided Losses to Crime Victims | $ 10.80 | $ 14.40 |

|---|

| Net Youth Earnings Benefit | $ 77.15 | $ 77.15 |

|---|

| Youth-Paid State and Local Taxes (10.9%) | $ 10.67 | $ 10.67 |

|---|

| Youth-Paid Federal Taxes (10.3%) | $ 10.08 | $ 10.08 |

|---|

| Net Benefit of Raising the Age | $ 66.80 | $ 74.10 |

|---|

Collateral Family and Community Benefits

In addition to the public safety benefit of reduced recidivism, raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction will have a positive economic effect, particularly on poor and disenfranchised communities throughout Illinois. Numerous studies demonstrate that persons convicted in the adult system face severely limited employment opportunities. In fact, serving time lowers a man's annual earnings by 40 percent. Furthermore, the higher recidivism rate of adult offenders, combined with their limited economic prospects, has severe negative effects on the communities to which they return. For example, the economic problems faced by former inmates "can also reduce the opportunities for and interest in employment among young men in poor neighborhoods who otherwise might not engage in crime." Moreover, these costs "are borne by offenders' families and communities, and they reverberate across generations." Indeed, children who have a formerly-incarcerated parent are thereby severely economically disadvantaged. Thus, the reduction in recidivism that will result from raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction will have important positive collateral effects on communities across Illinois.

Cost-Effective Programming Available in Illinois

Research consistently indicates the return on investment in evidence-based interventions with juvenile offenders. In fact, Illinois' juvenile justice system currently implements several cost-effective and evidence-based programs that will enhance recidivism reductions anticipated by the literature review and comparable cost-benefit analysis. Although some adult criminal courts have implemented a few discrete programs, youth in the juvenile justice system are routinely screened for family and social history, risk level, and mental health needs, in order to determine the most appropriate service delivery. Several programs and therapies available to youth in juvenile courts in Illinois are listed below. The cost-effectiveness of these programs, measured by return-on-investment (ROI), was recently assessed by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction and increasing the availability of these and similar programs, including through programs such as Redeploy Illinois, will result in more 17-year-olds engaged in these proven, cost-effective programs-access not meaningfully afforded to them through the adult system.

| Program | Return on Investment per $1 Spent |

|---|

| Multi-Systemic Therapy | $ 4.07 |

|---|

| Functional Family Therapy (inside institutions) | $21.57 |

|---|

| Functional Family Therapy (via probation) | $10.42 |

|---|

| Family Integrated Therapy | $ 2.51 |

|---|

| Aggression Replacement Training (via probation) | $20.70 |

|---|

| Victim-Offender Mediation | $ 6.94 |

|---|

Raising the Age of Juvenile Court Jurisdiction

The future of 17-year-olds in Illinois' justice system.

Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission

கருத்துகள் இல்லை:

கருத்துரையிடுக